Sister Nivedita and the Moral Imagination of a Nation

Long before the tricolour became our national pride, another flag quietly carried India’s hopes.

In 1904, decades before the tricolour was officially adopted, India witnessed the creation of what is now recognised as its first national flag design. It was conceptualised by Sister Nivedita, the Irish-born educator and disciple of Swami Vivekananda, who had come to see India not just as a cause—but as home.

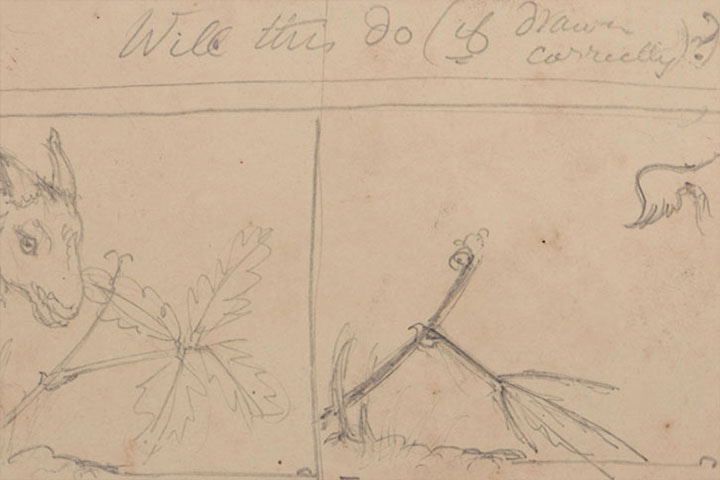

This flag was striking in its symbolism. It featured a red base, representing struggle, and a yellow border, signifying victory. At the center was a white lotus, symbolising purity, and above it, the vajra—an ancient Indian symbol associated with Lord Indra, and later in Buddhism, with spiritual power and unbreakable resolve.

Sister Nivedita interpreted the vajra as a symbol of selfless strength, once writing, “The selfless man is the thunderbolt. Let us strive only for selflessness, and we become the weapon in the hands of the gods.”

Some scholars believe that this idea of moral force—strength through selflessness—may have later shaped the visual language of India’s national symbols, including the Ashokan lions in the national emblem.

The words “Bonde Mataram” (বন্দে মাতরম্), written in Bengali script, were boldly inscribed across the flag—linking it to the spirit of Bengal’s cultural and political awakening.

Though never officially adopted, this was no ornamental design. It was a flag of conviction—an attempt to give form to India’s still-forming identity, rooted not just in resistance, but in moral imagination.

A Life of Commitment

Nivedita came to India in 1898 at the invitation of Swami Vivekananda. Within months, she had opened a girls’ school in Calcutta—a rare space for education in a time when girls were often denied such access. She taught in Bengali, visited students’ homes, and anchored her teaching in Indian ideas and traditions.

It is not by teaching a Bengali girl French, or the piano, but by enabling her to think about India, that we really educate her.”

– Sister Nivedita

Education, for her, was not about passing exams—it was about awakening character. “The training of the attention, rather than the learning of any special subject,” she wrote, “has always been, and still is, the chosen goal of Indian education.”

When plague struck Calcutta in 1899, she helped organise relief efforts—nursing the sick, collecting funds, and coordinating volunteers. She didn’t speak of service as charity. For her, it was an obligation of shared life—a form of citizenship before the word existed in any legal sense.

Unity as Ethical Practice

To Nivedita, India was already a nation—long before it had formal borders or statehood. “I believe that India is one, indissoluble, indivisible,” she wrote. “National unity is built on the common home, the common interest and the common love.”

She believed strength came not from power, but from conscience. “The strength of a nation is not in its armies, but in its character,” she wrote. And she didn’t see this as idealism—it was the foundation of her political thinking.

The vajra, which she placed on the flag, was her chosen symbol for this moral clarity. Not a sword, not a flame—but the thunderbolt that strikes from within, formed through discipline, duty, and service.

Culture, Knowledge, and Dignity

Nivedita’s work extended far beyond education. She was a vocal supporter of Indian scientists like Jagadish Chandra Bose, who faced institutional scepticism from British academic circles. She defended his work publicly, arguing that Indian traditions of science, observation, and thought deserved equal intellectual standing.

She also encouraged Indian artists to build a visual language of their own. Her support for Abanindranath Tagore’s painting Bharat Mata helped give visual form to a growing sense of cultural confidence. “From beginning to end,” she wrote, “the picture is an appeal, in the Indian language, to the Indian heart.”

In her essays—including The Web of Indian Life—she reflected deeply on caste, gender, ethics, and spiritual freedom. “The future of the nation depends upon the women,” she wrote. “And until the women are educated, the nation cannot be.”

She didn’t preach assimilation or nationalism for its own sake. Her vision was inclusive, philosophical, and practical all at once—rooted in the dignity of labour, education, and cultural memory.

A Quiet Legacy

Sister Nivedita died in Darjeeling in 1911, at the age of 43. Her grave bears a single line: “Here lies Sister Nivedita, who gave her all to India.”

And she did. She gave her health, her resources, her intellect, her friendships, and her presence. She didn’t seek power or recognition. What she offered was something slower, deeper: an ethic of service and a vocabulary of values.

She gave India its first national flag design—not merely to assert political identity, but to reflect a moral one.

Disclaimer: Some Images are AI generated

Sources: