Making a run for equality

Running is an accessible sport, but its history is fraught with inequality and exclusion. We remember the change-makers who made running a celebration of diversity

Running as an activity is meant to embrace people from all walks of life, irrespective of gender, age, or background. This inclusivity is particularly evident in the diverse participation seen in modern-day marathons, where elite athletes, casual runners, seniors, and children all share the same starting line.

Yet, despite its purported accessibility, running has not always enjoyed an unblemished history, particularly with regard to inclusion. Women runners, in particular, have endured significant challenges, and in recent times transgendered athletes have had to struggle to be included in the race.

The early 20th century saw women, widely stereotyped as the “weaker sex”, excluded from many long-distance events due to misconceptions about their physical capabilities.

Gatecrashing the boys’ party

In 1966, a female runner named Roberta Louise “Bobbi” Gibb, wearing white leather nurses’ shoes (running shoes for women had not yet been invented) joined the Boston Marathon unofficially. Wearing a hooded sweatshirt that hid her face, she finished with an impressive time of 3:21:40, but the record was not written into the books because she was an unofficial participant.

It took a sensational incident the following year for the barriers to fall.

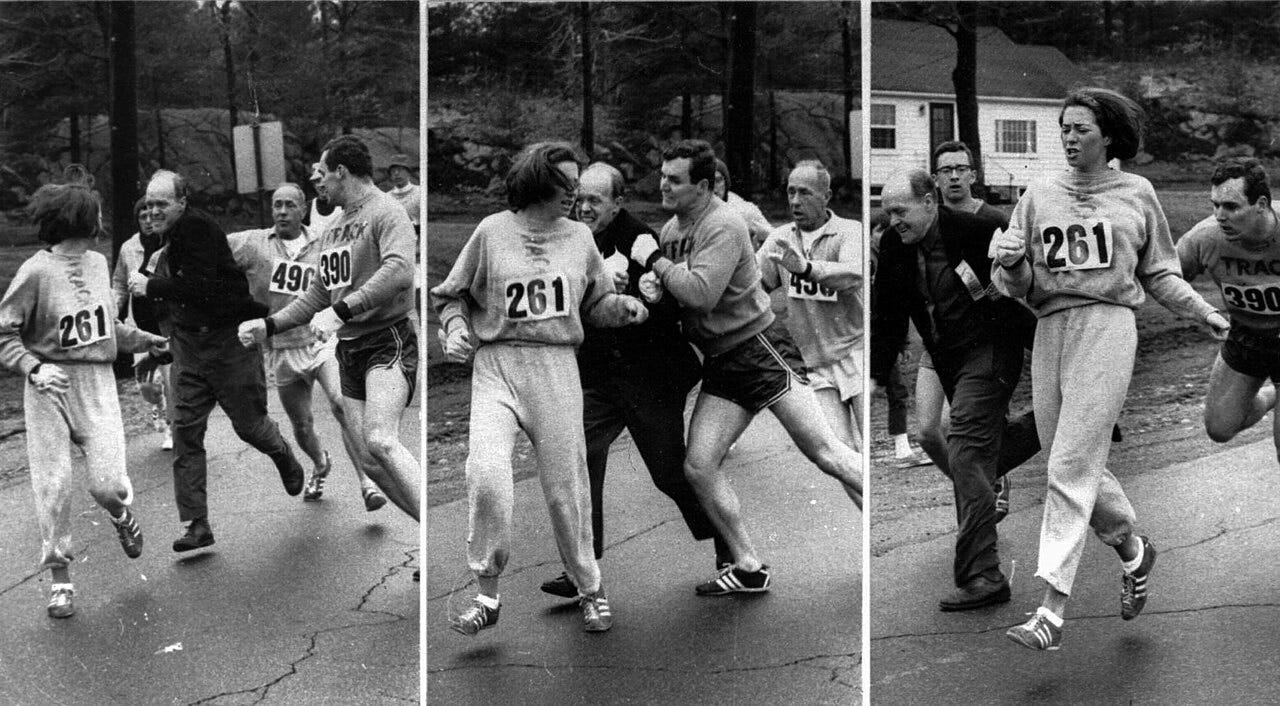

German-born American Kathrine Switzer had enrolled to run the 1967 Boston Marathon under the name of “K Switzer” and was assigned bib number 261 by officials who probably did not guess that she might be a female. Like Bobbi Gibb the year before, Switzer began the run in a hooded sweatshirt that covered her head. Moments into the race, the hood slipped off, and it became apparent that Switzer was a woman. At the 4-mile mark, race official Jock Semple leapt off a press truck and attempted to rip off her race number to forcibly prevent Switzer from running the marathon as an official participant. Switzer’s boyfriend, a burly athlete who was also running the race with her, succeeded in pushing Semple away, which enabled her to complete the marathon. The photographs of the incident drew much media attention.

Race for equality

Following the episode, Switzer committed herself to enabling other women to participate in the race. In 1972, the Boston Marathon made room for an official women’s race. In 1974, Switzer was the women’s winner of the New York City Marathon. She returned to the Boston Marathon in 1975 to record her personal best time of 2:51:37. She was declared the Female Runner of the Decade (1967-77) by Runner’s World magazine. In 1978, Switzer established the Avon International Running Circuit, a series of women-only races held in 27 countries. These events, including seven international women's marathons, attracted top female runners and helped make the case for including the women's marathon in the Olympics. In 1984, the Los Angeles Olympics officially included the women's marathon. At the games, Switzer returned in a new avatar as a television commentator and received an Emmy Award for her work. Her memoir, Marathon Woman, released in 2007, won the Billie award for journalism.

The challenges of inclusion are not limited to women. In recent times, LGBTQ and transgender individuals have also faced hurdles in competitive running. For transgender athletes, particularly, the path to participation is fraught with regulatory and societal barriers. Many race organisations continue to require transgender athletes to undergo hormone treatments or gender reassignment surgery to compete in the category that aligns with their gender identity. Such policies, coupled with social stigma, can make it difficult for transgender athletes to feel fully welcomed in the running community. However, recent efforts, such as the introduction of non-binary categories in major races like the New York City Marathon, mark a significant step towards inclusivity.

Advocacy from within the running community is also on the rise, with groups emphasising the importance of inclusive practices and gender diversity. The International Olympic Committee recently revised its guidelines to ensure that transgender athletes can compete without undergoing invasive medical treatments.

Listen to Run Bhoomi, Ep 3 of our series Economies Of Khel on Radio Azim Premji University

Running heals our wounds

As running becomes inclusive, it offers a model for how society can embrace diversity. It can even mend fences and build friendships through reconciliation, as the story of Kathrine Switzer and Jock Semple goes. As Semple became accepting of women’s participation in sports, the two eventually put their differences aside and became good friends until his death in 1988.

The gap between our love for running and our quest for equality has been narrowing with time, and when we breast the finish line, it will be the sweetest victory, won’t it?